Acknowledgements

The OECD Digital Government Policy Framework policy paper was prepared by the Directorate for Public Governance (GOV), under the leadership of its Acting Director, Janos Bertok.

This policy paper was produced by GOV’s Open and Innovative Government Division (OIG). It was written by Barbara-Chiara Ubaldi, Acting Head of the Open and Innovative Government Division and Head of the Digital Government and Open Data Unit.

This paper benefited from the expertise and inputs from Edwin Lau, Senior Counsellor to the Director for Public Governance; João Ricardo Vasconcelos, Arturo Rivera Pérez, Benjamin Welby and Felipe González-Zapata, Policy Analysts, Digital Government and Data Unit; and Mariane Piccinin Barbieri, Consultant, Digital Government and Data Unit.

The author is grateful for the comments and feedback from Marco Daglio, Head of the Observatory in Public Sector Innovation; Jamie Berryhill, Policy Analyst, Observatory in Public Sector Innovation; Alessandro Bellantoni, Head of the Open Government Unit; and Karine Badr and David Goesmann, Policy Analysts, Open Government Unit. The author is also thankful to Andrea Uhrhammer and Amelia Godber for editorial assistance.

- Introduction: The OECD Digital Government Policy Framework

Driving the transformation

The COVID-19 pandemic has underscored the importance of digital technologies and data in building economic and social resilience through strategic, agile and innovative government approaches. Digital technologies and data have played a vital role in managing the crisis and supporting societies and economies in countries with strong digital government foundations1 (OECD, 2020[1]). Where digital technologies or data were not used strategically or effectively, the COVID-19 crisis has highlighted gaps and inequalities, and exacerbated challenges (OECD, forthcoming[2]; OECD, forthcoming[3]). In all cases, this crisis should encourage governments to share key lessons regarding key digital enablers and critical digital deficiencies.

Governments worldwide are facing decreasing levels of public trust (OECD, 2019[4]), while simultaneously experiencing growing exponential and rapid changes brought about by the advent of the digital age – an age characterised as “open, digital and global rather than closed, analogue and local” (Benay, 2018[5]). The COVID-19 pandemic and the multidimensional crisis it has provoked have disrupted governments; however, they also offer an opportunity to revisit strategic approaches on the use of digital tools and data to improve the delivery of public value. Governments must strengthen their capacities to react promptly in the event of subsequent waves, or future crises, and design recovery strategies that are equitable and sustainable, and contribute to long-term public sector reform. Leveraging this opportunity requires understanding how to take meaningful decisions for digital government in the light of domestic contexts, rather than simply accelerating the digital transformation of the public sector. Such a strategic approach undertaken as consequence of this pandemic will shape reforms and actions that will drive the use of digital technologies and data in the public sector for years to come.

A successful digital transformation will enable public sectors to operate efficiently and effectively in the digital environment, and to deliver public services that are simpler and more effective (Greenway et al., 2018[6]). However, fully realising this digital transformation requires a paradigm shift from e-government to digital government, as underscored by the 2014 OECD Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies (OECD, 2014[7]).

According to the Recommendation, digital government is understood as “the use of digital technologies, as an integrated part of governments’ modernisation strategies, to create public value” (OECD, 2014[7]). Since its adoption, the Recommendation has been applied in numerous digital government reviews to support the analysis and frame the formulation of policy recommendations to help governments make the shift from e-government to digital government.

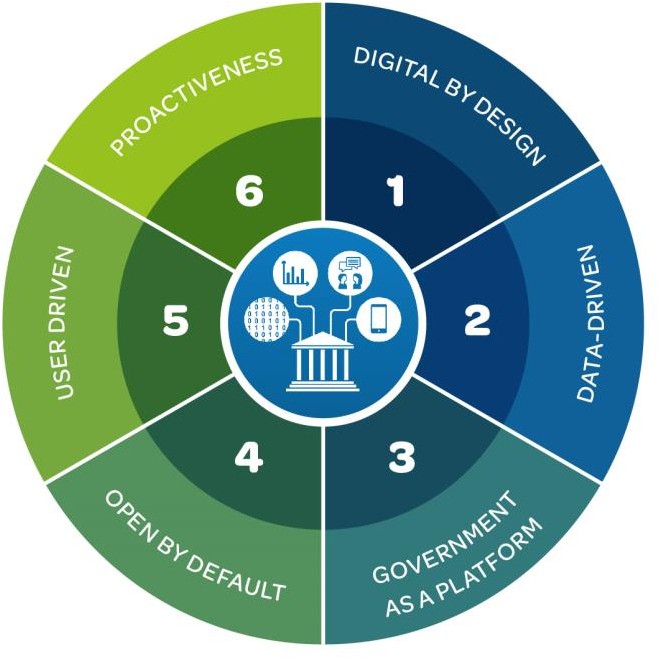

This analytical work inspired and facilitated peer learning and helped identify the essential characteristics of a digital government. These characteristics constitute the OECD Digital Government Policy Framework (DGPF). Presented to E-Leaders during the 2018 meeting in Korea, the DGPF consists of six dimensions that comprise a fully digital government:

- Digital by design

- Data-driven public sector

- Government as a platform

- Open by default

- User-driven

Building agile and adaptable government

Figure 1.1. The OECD Digital Government Policy Framework0The DGPF (Figure 1.1) is a policy instrument designed to help governments identify key determinants for effective design and implementation of strategic approaches for the transition towards digital maturity of their public sectors. The DGPF supports qualitative and quantitative OECD assessments across countries and individual projects. It is applied in peer reviews and frames the methodology and survey design of the OECD Digital Government Index (DGI) which measures countries’ digital government maturity across the six dimensions (OECD, 2020[8]).

The DGPF builds on the provisions of the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies (2014[7]) to advance the maturity of the six dimensions. This process emphasises levers, institutional models and initiatives that help overcome bureaucratic legacies, verticality and silos, and fosters horizontality, integration, co-ordination and synergies across and between levels of government. This represents a paradigm shift in the governance of digital government and public sector data, and is essential in order to progress beyond the idea of digital services as isolated outputs and secondary effects of individual policies. Under the new paradigm, digital services are core, overarching enablers of public sector transformation (OECD, forthcoming[9]) since public services the most immediate experience that people have of their government

Understanding that governments do not design public services to serve an organisation, a stakeholder or a machine, but rather as a response to people’s needs, underpins the drive to rethink internal processes and operations with a view to connecting different parts of the administration to improve efficiency, effectiveness and user experience, and to strengthen trust in government (Downe, 2019[10]). A digital government that presents higher levels of maturity across the six-dimensions is better placed not only to achieve internal efficiencies and transparency, but also to deliver public services that match and potentially exceed people’s expectations.

However, above all, the DGPF recognises that a digital by design approach will act as a strategic lever for digitalisation policies across public sectors, creating the context for embedding the other foundational dimensions of a digital government within the policy-making process, as well as in sectorial and cross- cutting digital projects and initiatives. This approach promotes a coherent and more sustainable digital transformation of the public sector capable of delivering better value. Having a government that is digital by design can and should be embraced by governments as a critical part of the broader public sector modernisation and digital transformation agenda.

Fostering governments that are more digitally mature according to the six dimensions of the OECD DGPF will contribute to reshaping interactions between governments and the public through expanded stakeholder engagement, better equipped teams, more empowered civil servants, enhanced accountability across the public sector and new ways for collective intelligence to grow. The COVID-19 crisis has demonstrated the critical importance of connected and collaborative governments capable of leveraging collective intelligence and networked societies – governments that are more agile, transparent, responsive and accountable. Digital tools and data have proven to be key assets for decision makers seeking to help public sector organisations evolve. The DGPF provides the groundwork to advance these transformative efforts, to respond to the needs of economies and societies, and to build agile and adaptable government.

- 2. Digital by design

A government that is digital by design establishes clear organisational leadership, paired with effective co-ordination and enforcement mechanisms where “digital” is considered not only as a technical topic, but as a mandatory transformative element to be embedded throughout policy processes

Embedding “digital” in the policy lifecycle

For the digital transformation of government to succeed, digital technologies must be fully embedded in policy making and service design processes from the outset. The public sector needs to be digital by design. This implies mobilising existing and emerging technologies and data to rethink and re-engineer business processes and internal operations. The aim is to simplify procedures, innovate public services, and open up multiple channels of communication and engagement with the public and private sectors, the third sector and the public. This is essential in order to foster public sectors that are not only more efficient in creating public value but also capable of delivering more sustainable and citizen-driven policy results.

Over recent decades, the governments of OECD member and partner countries have increased their efforts to digitise public sector processes and services, introducing technologies in different public sector activities. This cross-cutting commitment has generated numerous efficiencies in public sector internal operations and external communications, but has tended to apply digital technologies on top of analogue processes and services. In many cases, such efforts have effectively digitised the existing Weberian bureaucracy and reproduced in digital form existing silos and government-centred approaches.

A shift from an e-government to a digital government approach is required to embed “digital” throughout the policy lifecycle. Rather than digitising analogue methods, digital governments exploit new opportunities introduced by the digital transformation to enable an end-to-end positive rebooting of policy and service design and delivery processes.

Leading and co-ordinating the transformation

Successful digital transformation of the public sector requires cross-sector and cross-level efforts to achieve a coherent and sustainable digital government. Governance plays a critical role here. In line with the E-Leaders Governance Handbook’s framework (OECD, forthcoming[9]), an approach that is digital by design requires clear leadership and effective co-ordination mechanisms with robust strategies, management tools and regulations, to ensure that “digital” is considered not merely as a technical topic, but also as a mandatory transformative element to be embedded throughout service design and policy processes (OECD, forthcoming[]). Updated institutional arrangements that define a leading public sector organisation and lead government roles, such as Chief Information Officer (CIO) and Chief Data Officer (CDO), are also essential to secure increased understanding and use of digital technologies as a transformative element of public sector activities (OECD, 2019[11]).

OECD countries are progressively updating institutional models to better drive the digital transformation, through the institutionalisation of public sector organisations with a cross-cutting digital government mandate2 (OECD, 2016[12]). Improved institutional models, strengthened by co-ordination and compliance mechanisms and supported by policy levers3 that promote a digitalisation agenda across the public administration, enable the alignment and inclusive development of digital government policy with diverse public sector reform agendas. The institutionalisation of policies to incorporate digitalisation within new regulations or legislative procedures is a particularly effective mechanism to promote digital by design approaches.4

Technological development and necessary capacities

A digital by design culture requires governments to be technology agnostic but fully aware of existing digital opportunities for improved functioning of public sectors and better public value creation. A digital government needs a public sector able to tackle technical legacy challenges in order to provide the basis for rapid technological development and the progressive digitalisation of different government activities, ranging from education to defence, and from health to justice and social protection. An integrated policy approach is therefore necessary to overcome silos between digital policies and other policy domains. Interoperability and common standards are likewise essential to secure coherency and synergies across different public efforts,5 to avoid wasteful duplication and overlap, and to foster joined-up administrations (see section 4).

Digital by design governments require a senior leadership aware of the benefits of technologies, as well as of their potential disruptive role in relation to the development of public sector activities. For instance, in the context of the digital transformation, emerging technologies (ET), such as artificial intelligence (AI) and Blockchain, carry a significant disruptive potential (Ubaldi et al., 2019[13]). The incorporation of these and other technologies into the design of policies and services from the outset can help generate improved human and organisational capacities for information and knowledge management, especially for service design, and favour more convenient and tailored delivery.

Nevertheless, the ubiquitous presence of digital technologies throughout government activities requires a strong commitment to improving the skillset of public officers. This implies attracting and maintaining IT professionals in the public sector as well as developing the specialist skills of those already in the public sector workforce. Furthermore, it is necessary to enhance digital government user skills among all public officials in order to spread a digital mindset throughout the public sector workforce. Such an approach will ensure broader awareness of the opportunities, benefits and challenges of the digital transformation (OECD, 2019[14]; OECD, forthcoming[15]).

Digital means simple and collaborative

Capturing the potential of digital technologies and data in the early design stages of processes and services represents an important opportunity to rethink the transactional interactions between users and the state. Public sectors have the opportunity to transform procedures, simplify administration, reengineer workflows, and reimagine whole services based on an understanding of user needs and consideration of dependencies across different sectors and levels of government (see section 6).

Digital by design approaches also favour the use of technologies for improved collaboration with stakeholders at different stages of the policy and service lifecycle. Government as a platform and user- driven policies allow for improved efficiency and the development of tailored services based on joint ownership and shared responsibility with civil society (see section 4 and section 6).

Securing digital inclusiveness

Although digital by design implies the design, development, management and monitoring of internal government processes to fully mobilise the potential of digital technologies and data, this is not equivalent to delivering digital by default administrations and services to constituents. An omnichannel approach will enable a more inclusive digital transformation, allowing online and mobile services to co-exist with face-to- face or over-the-phone service delivery, ensuring that underlying processes are digitally coherent and integrated (OECD, 2020[16]). This implies digitally assisted delivery of public services across all channels, in order to secure the same level of quality regardless of the chosen means of access. Digital by design should not be confused with digital by default, where services are preferentially delivered online, as the latter approach has the potential to generate discrimination against segments of the population with limited online access or ability to use digital technologies (see Figure 2.).

Figure 2.1. Digital by design vs digital by default

A government that is digital by design focuses on securing the assisted on of Service italisation of Service Delive

DigitalisaApproaches Digitalisation ofDelivlisati

A government that is digital by design focuses on securing the assisted delivery of digital services, as seen in Norway, Portugal and the United Kingdom (Box 2.1). When services work seamlessly across different channels, the public sector is able to continue investing in and benefiting from digitalisation, while simultaneously working to ensure that no citizen is left behind due to uneven access or lack of skills necessary to use digital technologies.

Box 2.1. Digital by design country practices

Administrative modernisation review of legal and regulatory initiatives (Portugal)

In Portugal, the Agency for the Administrative Modernisation (AMA) provides inputs on new legal and regulatory initiatives coming before the Portuguese government for approval, in order to promote an administrative modernisation approach across sectors and levels of government. AMA reviews relevant regulations, decrees and resolutions of the Council of Ministers, and suggests the inclusion of digital instruments and principles considered critical to the country’s administrative modernisation agenda. Examples include the reuse of data, application of the Once Only Principle, and use of the national interoperability platform and digital identity platform autenticação.gov.

This transversal cross-cutting approach benefits from high-level political support from the Minister of the Presidency and Administrative Modernisation. This AMA to improve alignment and secure a coherent digital by design policy across the entire national public administration.

Impact assessment of legal projects on ICT (Austria)

In 2012, the Austrian government developed a public guide to advise legal experts responsible for drafting laws on the integration of digital technologies, including relevant regulatory issues. Legal experts across the public sector (at both federal and sub-national government levels) benefit from common guidance on how to incorporate digital technologies at the outset when drafting legislative proposals. As a result, the need for central interventions by the Federal e-Government Department during the legislative process has decreased considerably, as draft legislation already takes their recommendations into account.

Government Digital Service (United Kingdom)

The Government Digital Service (GDS) was founded in December 2011. It forms part of the Cabinet Office, the United Kingdom’s centre of government, and works across the whole of the UK government to help departments meet user needs and transform end-to-end services. The responsibilities of the GDS are to:

- Provide best practice guidance and advice for consistent, coherent, high-quality services.

- Set and enforce standards for digital services.

- Build and support common platforms, services, components and tools.

- Help government choose the right technology, favouring shorter, more flexible relationships with a wider variety of suppliers.

5.Lead the Digital, Data and Technology function for government.

- Support increased use of emerging technologies by the public sector

GDS administers a number of standards, including the Digital Service Standard, the Technology Code of Practice and the Cabinet Office spending controls for digital technology. To support teams in meeting their expectations, GDS works with cross-government practitioner networks to curate guidance and resources through the GOV.UK Service Manual and the GOV.UK Design System. GDS is also responsible for operating several cross-government common components including GOV.UK, GOV.UK Verify, GOV.UK Pay, GOV.UK Notify and the Digital Marketplace (see section 4).

X- Road (Estonia)

Estonia’s X-Road is a government platform that supports data sharing between over 900 organisations and enterprises in Estonia. The platform secures the delivery of services to citizens and companies through access to databases, the creation and transmission of large datasets, and online searches.

Platform security is ensured through digital identification, multi-level authorisation, a high-level log processing system and encrypted data transfers. The system provides an ingenious solution to the issue of data ownership – its decentralised nature allows participating institutions to retain ownership of their data, but allows them to share data or access the data of other institutions as necessary.

Coupled with the Once Only Principle, the system has facilitated increased co-operation and data sharing between institutions, leading to cost-reductions and increased efficiency.

“Digital First Choice” initiative (Norway)

In Norway, the Digitalization Memorandum agreed that communication between the public sector and citizens and businesses should be conducted via digital online services. Such services should be comprehensive, user-friendly, safe and universally designed. To achieve this goal, the Memorandum called for ministries to map the potential for digitising services and processes, and to prepare plans for making appropriate services available digitally. Ministries should also identify services that need to be considered in conjunction with other services and their suitability for developing service chains. Plans to establish joined-up services should be developed.

The mapping process determined which services had already been digitalised and which were suitable for digitalisation. It also assessed whether existing digital services were user-oriented and user-friendly, or whether they should be re-designed, simplified or even eliminated

The right to communicate digitally with the public sector (Spain)

In June 2007, the Spanish Parliament passed Law 11/2007 enshrining people’s right to communicate with public service administrations online. The law formed the basis for Spanish e-government and has enabled progressive work in this area. Its most important provisions entitle citizens:

- Guaranteed digital service provision, whereby public administration bodies ensure that all government transactions and services are fully available and updated

- The right to choose among available service channels when communicating with public authorities. The authorities are required to provide both analogue and digital communication and service processes as requested by

- The right to equality of access to public online services. Government services should not discriminate against citizens using non-electronic forms of communication and

Ongoing efforts have ensured additional laws and royal decrees that have further promoted digitalisation across all areas of government.

Citizen Spots (Portugal)

In order to advance the multichannel delivery of public services in Portugal, the government has prioritised the development of small and integrated one-stop shops, which provide central and local administration services as well as those of utility providers (e.g. Electricity, Telecommunications). These counters, which are managed by public officials, assist citizens in accessing online public services.

Developed in partnership with municipal governments and the main national postal company, the network of Citizen Spots allows the Portuguese government to reach segments of the population that lack access to the Internet or the necessary skills to use online services. At a relatively small investment, the network also covers remote areas where face-to-face delivery of public services would otherwise pose a financial challenge.

3.Data-driven public sector

A data-driven public sector recognises and takes steps to govern data as a key strategic asset in generating public value through their application in the planning, delivering and monitoring of public policies, and adopts rules and ethical principles for their trustworthy and safe reuse

Data as a foundational enabler of digital governments

A data-driven public sector recognises and takes steps to govern data as a key strategic asset in generating public value through their application in the planning, delivering and monitoring of public policies, and adopts rules and ethical principles for their trustworthy and safe reuse.The digital age has magnified the importance of data as a foundational enabler of digital governments, helping public sector organisations to work together to forecast needs and understand how to respond to change and shape delivery (see section 4). In recent years, the exponential generation of data combined with the widespread take-up of mobile devices and the rapid evolution of emerging technologies have shown great potential to improve the internal operations of public sector organisations and their approach to the design and delivery of policies and services (Ubaldi et al., 2019[13]). This trend will undoubtedly continue to affect governments globally. Governments who want to achieve higher levels of digital maturity must therefore take key actions to secure the efficient and ethical use of data in order to achieve transformative goals. Hence, a mature digital government is a data-driven government.

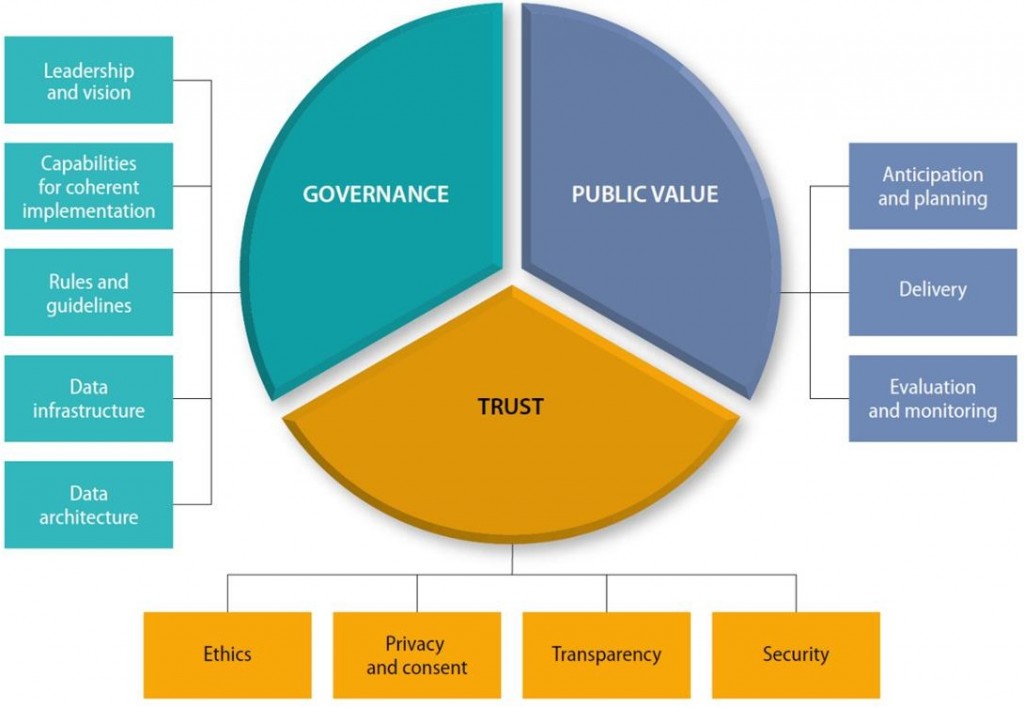

Building on previous OECD work about the role of data in society and the economy, the OECD report The Path to Becoming a Data-Driven Public Sector (2019[11]) proposed a model to help understand how a “data- driven government” can maximise the opportunities provided by 21st century (see Figure 3.1). According to the model, a truly data-driven government:

- recognises and governs data as a key strategic asset, defines its value, measures its impact, and reflects active efforts to remove barriers to managing, sharing and reusing data

- applies data to transform the design, delivery and monitoring of public policies and services

- values efforts to publish data openly and the use of data between, and within, public sector organisations

- understands the data rights of citizens in terms of ethical behaviours, transparency of usage, protection of privacy and security of data.

In particular, a data-driven government focuses on applying data to generate public value through three types of activity:

- Anticipation and planning – using data in the design of policies, the planning of interventions, the anticipation of possible change and the forecasting of needs.

- Delivery – using data to inform and improve policy implementation, the responsiveness of governments and the provision of public services.

- Evaluation and monitoring – using data to measure impact, audit decisions and monitor performance.

Figure 3.1 The 12 facets of a data-driven public sectỏr

Data governance

The COVID-19 crisis has demonstrated the crucial role of data for government readiness to formulate immediate responses and inform sustainable and equitable recovery strategies. Facilitating access, sharing and reuse across the whole ecosystem has helped amplify the role of data to foster joined-up decisions and collective actions to navigate this pandemic. Nevertheless, some governments have given the impression of rolling back transparency measures, while others have moved in the opposite direction, disaggregating data to unprecedented levels, but not always adopting a convincing approach to balancing potential risks with expected benefits. As mutual trust between the public and governments is a crucial element in fighting the pandemic, and one that can be undermined by inadequate efforts to secure ethical and trustworthy use of data, demonstrating appropriate models for data management is of particular importance in this moment of crisis.

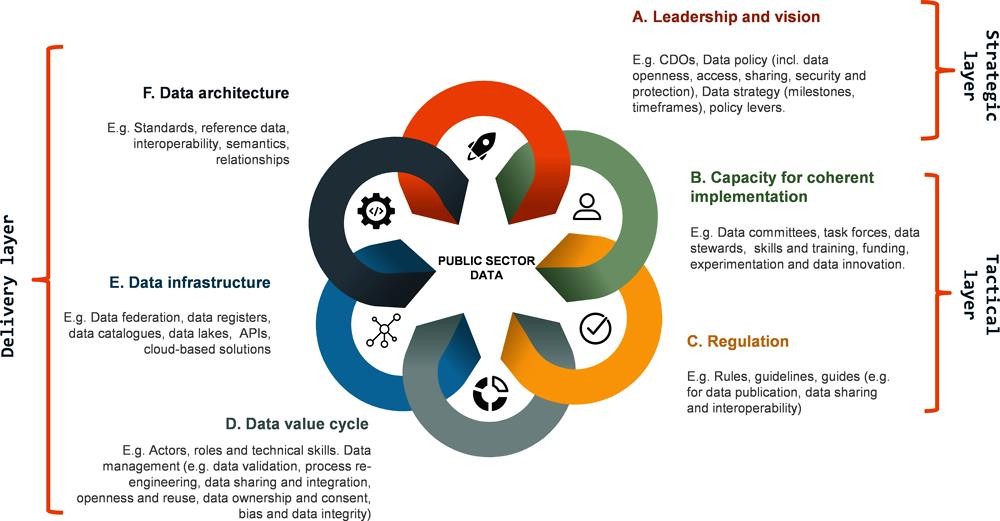

A data-driven government adopts a whole-of-government approach, drawing on a coherent and comprehensive model of data governance to deliver better policies and services, while endeavouring to be efficient, transparent and trustworthy in the use of data. As shown in Figure 3.2, the key components of a comprehensive data governance framework are as follows:

- Secure the leadership and vision to ensure strategic direction and purpose for the data-driven conversation throughout the public

- Encourage the coherent implementation of this data-driven public sector framework across government as a whole and within individual

- Put in place, or revisit, the regulation (rules, laws, guidelines and standards) associated with

- Integrate the data value cycle addressing the specific policy implications and opportunities of each stage (from data generation and collection to reuse).

- Develop the necessary data infrastructure to support the publication, sharing and reuse of

- Ensure the existence of a data architecture that reflects standards, interoperability and semantics throughout the generation, collection, storage and processing of

Figure 3.2. Data governance in the public sector

Data-driven approaches reinforce trustworthinessThe develoment of such a holistic, coherent and scalable approach to data governance that underpins a truly data-driven public sector, and reflects the critical elements for achieving system-wide benefits in government, can secure the efficient and ethical management, access, sharing and use of data (see section 5). Adequate data governance can also favour the use of alternative sources of data in the evaluation and monitoring of government performance, with a view to delivering policies and services over time, and supporting continuous improvement in response to feedback and data on usage and satisfaction. Accordingly, data governance can help public sector organisations anticipate, prioritise and meet user needs (see section 6 and section 7)

Public trust in governments is critical for citizen well-being, but is far easier to lose than to build (Welby, 2019[18]; OECD, 2017[19]). The way in which governments handle citizen data can be particularly damaging in terms of public trust. Therefore, establishing an adequate governance framework is essential in order to tap into the value of data, to anticipate and respond to the needs of users, to deliver better services and policies, and to allow data integration, access, sharing and use across the public sector – in ways that reinforce rather than erode public trust (OECD, 2019[20]; OECD, 2019[11]). Recognising the linkage between trustworthy use of data and confidence in the public sector, the OECD report, The Path to Becoming a Data-Driven Public Sector (2019[11]), challenges governments to:

- adopt an ethical approach to guide data-driven decision making and service design and delivery

- protect privacy, promote transparency and design user experiences that help citizens understand and grant or revoke consent for their data to be used

- approach the security of government services and data in ways that mitigate risks without blocking the transformation of the public sect

Engaging the ecosystem

Although governments around the globe have prioritised the creation of overarching frameworks to build more data-driven public sectors, there remain many barriers to the full optimisation and maximisation of government data (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2020[21]). Realising the full benefits of data-driven approaches to foster more productive, accountable and inclusive governments, will require not only the establishment of sound governance models, but also the recognition of fault lines in existing data ecosystems and engagement with all actors to build a critical mass of good practices.

This approach can help create a common user experience that most actors will want to replicate. It will also foster a sense of familiarity with data-driven approaches not just among specialised civil servants, such as data analysts, but also more broadly in the public sector workforce. For a public sector organisation to become truly data-driven, interactions with data cannot remain the responsibility of “data evangelists”. Placing data together with digital technologies at the centre of digital transformation strategies will be essential to building governments that are digital by design (see section

Box 3.1. Data-driven country pract

A comprehensive national government data strategy (the Netherlands)

Data Agenda Overheid is the Netherland’s national government data strategy developed and led by the Dutch Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations. The strategy aims to accelerate the ethical use of data within central and local governments in order to foster better policy making and resolve social challenges, paying specific attention to legislation and public values, data management, knowledge sharing, and investment in people, organisations and cultural change.

Promoting institutional data leadership and maturity (United States)

In accordance with The Foundations for Evidence-Based Policymaking Act of 2018 and Memorandum M-19-23, all US federal government agencies are mandated to designate a Chief Data Officer responsible for activities aimed at leveraging better use of government data. Institutional Chief Data Officers will head a newly instituted Data Governance Body inside their respective agency, which will decide and enforce priorities for managing data as a strategic asset.

Applying data to predict health service needs (Australia)

To help Australian hospitals meet their target of treating emergency department patients within four hours, the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation developed the Patient Admission and Prediction Tool (PAPT). Using the hospital’s historical data, it can provide an accurate prediction of expected patient load, medical urgency and specialty, and the number of admitted and discharged patients. PAPT is being expanded to predict diseases such as influenza and hospital admissions of patients with chronic diseases. The tool is currently in use in 30 hospitals and has shown a 90% accuracy rate in forecasting bed demand. If rolled out across Australia, this rate would equate to AUD 23 million in annual

Appointing an independent entity to ensure ethical use of data (New Zealand)

In order to balance increased access and use of data with appropriate levels of risk mitigation and precaution, the government Chief Data Steward in New Zealand founded the so-called Data Ethics Advisory Group. The main purpose of this body is to assist the New Zealand government in understanding, advising and commenting on topics related to new and emerging uses of data. To ensure that the advisory group delivers on its purpose, the government Chief Data Steward has appointed seven independent experts from different areas relevant to data use and ethics as members, including experts in privacy and human rights law, technology and innovation. One of the positions is reserved for a member of the Te Ao Maoru Co-Design Group as way to support Maori data governance work and ensure the inclusion of different perspectives in the New Zealand data governance framework.

Ethics through an ethical framework (UK)

In the United Kingdom, the Data Ethics Framework provides a foundation for work in the field of data science. Principle 6 of this framework states that all activity in this field should be as open and accountable as possible. While the framework is not formally mandated, it is consistent with the United Kingdom’s approach to disseminating best practices throughout the public sector in terms of the Service Standard and the Service Manual. The framework is supported by the commission given to the UK Office for Artificial Intelligence to explore the use of algorithms and other techniques, such as machine learning, to transform government and aid decision making. The UK government also collaborates with external academic and research institutions in industry including the Alan Turing Institute, the Open Data Institute, the Open Government Partnership and the Policy Lab

Regulatory efforts to promote data ethics (Korea)

The Personal Information Protection Commission of Korea is required by law to establish a master plan every three years to ensure the protection of personal information and the rights and interests of data subjects. Furthermore, the heads of central administrative agencies must establish and execute an implementation plan to protect personal information each year in accordance with the master plan. Any change to policy, systems or statutes requires an assessment of the possibilities of data breaches, which are then openly published. This approach demonstrates the importance accorded to addressing privacy and transparency issues in Korea.

- 4. Government as a platform

A government acts as a platform for meeting the needs of users when it provides clear and transparent sources of guidelines, tools, data and software that equip teams to deliver user-driven, consistent, seamless, integrated, proactive and cross-sectoral service delivery

Delivering the digital transformation at scale

Governments are increasingly redesigning services to focus on the needs of their citizens in ways that take advantage of data, the Internet and digital technologies. Given the scope and complexity of the public sector, there is a risk that the transformation of government services may happen in piecemeal fashion over an extended period rather than delivering in a timely manner at the scale, coherence and effectiveness required. Rather than approaching transformation on a service-by-service basis, the proposed government as a platform model allows for transformation to scale by creating an ecosystem that lets service teams focus on the unique needs of their users (OECD, 2020[16]). By focusing on delivering the basics, this approach lays the foundations for more ambitious expressions of government as a platform, fostering different models of delivery with those outside government and ultimately rethinking the relationship between citizen and state.

In 2010, Tim O’Reilly, the founder and CEO of O’Reilly Media, Inc, reflected on the idea of government as a platform, while considering the evolution of the Internet and its role in the delivery of government (O’Reilly, 2011[22]). Central to his hopes for the future was the opportunity offered by the democratising potential of the Internet (exemplified by the rise of social media) to harness the knowledge and experience of citizens to address challenges facing society. The idea of Government 2.0, which he went on to explore, is defined as “the use of technology – especially the collaborative technologies at the heart of Web 2.0 – to better solve collective problems at a city, state, national and international level” (O’Reilly, 2011[22]). It anticipates scenarios where people participate in the ongoing business of governance and service delivery– not just with a vote from one ballot box to the next. This concept is elaborated in the 2017 OECD Recommendation of the Council on Open Government (OECD, 2017[23]) which supports the creation of “a culture of governance that promotes the principles of transparency, integrity, accountability and stakeholder participation in support of democracy and inclusive growth”. While some expressions of open government give the impression of greater public involvement, O’Reilly argues that these merely produce “collective complaint” (exemplified by the increasing availability of e-petitioning platforms), with the public reacting to government behaviour rather than becoming a proactive partner.

Instead, O’Reilly frames the situation as a choice between a “Cathedral” and a “Bazaar”. Rather than a government that distributes services controlled by a few (a Cathedral), he imagines an open community where different providers offers a variety of services from which people can make a choice (a Bazaar) (O’Reilly, 2011[22]). In the latter model, he argues, government regulates and builds infrastructure, but the value comes from the traffic flows and the public or private entrepreneurs and businesses the infrastructure supports. In the digital space, a similar parallel is drawn with technologies that rely on satellite infrastructure such as weather, communication and positioning. Only governments could support the initial investment required for infrastructure, but once built such infrastructure opens up opportunities to innovate inside and outside the public sector (e.g. the delivery of new public services or the emergence of commercial opportunities in the competitive marketplace).

This model of government argues that it is possible to arrive at an irreducible core of essential, foundational infrastructure on top of which public and private developers would innovate, with the role of government being to enforce regulations and to ensure that the constituent elements function well together. However, there is an inherently political slant to this argument. Citing the origins of healthcare, education, infrastructure and other achievements of local collectives, rather than the state, invokes an argument about the size of government at those points in history without discussing the limitations of things we now take for granted, such as suffrage, taxation models, representation and the challenges of pre-communication revolution technologies. Furthermore, given the expectation of universality of provision of services, is such an idea of essential, foundational infrastructure plausible? In many cases, citizen or market-led activity occurs as a reaction to a problem when there is sufficient motivation or financial incentive to take action. In the case of government, the need to address issues and provide services in some cases must often anticipate demand and precede requests for action (see section 7).

The origin of the phrase “government as a platform” arises from a desire to transform the structures of government as a foundation for realising the potential of “Government 2.0”. Inspiration is drawn from the ecosystems created by Google and Apple to support their mobile operating systems, with government services enabled by a core set of reusable digital components and/or intermediated by a range of providers competing with one another. However, although this thinking has become part of the narrative for digital government leaders, its interpretation and translation into concrete actions embedded in digital government strategies has diverged somewhat to hinge instead on the needs that those actions are expected to meet

A sequential and iterative approach to building government as a platform

A digital government that adopts a government as a platform approach could therefore be expressing any of the following three models:

- Government as a platform: an ecosystem that supports service teams to meet needs. Here the focus is on the underlying challenges of government service provision facing public service teams. Critically, this requires the building of an ecosystem, step by step, to support and equip service teams to meet the needs of users, while encouraging collaboration with citizens, businesses, civil society and others. This approach draws on a digital ecosystem for tooling, guidance and governance in the digital age to help teams avoid the constraints and costs of transforming services one by one; and, instead, design and deliver high-quality services at scale,and in particular resource teams that might lack capability, budget or visibility. This approach results in improved and coherent outcomes across and between levels of government, and a better and consistent experience of the state for citizens.

Government as a platform: a marketplace for public services. This interpretation of the idea focuses on creating a marketplace for public, private and third sector delivery of services enabled by a strategic approach to data sharing, a trusted consent model for handling citizen data, open standards for interoperability and mechanisms for quality assurance. Assuming that such a foundation exists for multiple actors to contribute to the provision of public services, different approaches to a given problem can be explored, providing citizens with the freedom to choose the approach which best works for them, and alleviating pressure on government to deliver.

Government as a platform: rethinking the relationship between citizens and the state. At this level of maturity, the adoption of government as a platform intersects with the Recommendation of the Council on Open Government (OECD, 2017[23]) and the transformational ambitions of the user- driven dimension of the DGPF (see section 6). Here, at its most mature, government as a platform is expressed as a commitment to revisiting the participation of citizens in public governance and public service, heralding a more co-operative and collaborative experience of government, underpinned by the opportunities provided by new and emergent digital technologies and data. This will manifest itself in the creation of online and physical habitats (e.g. Labs) for multi- stakeholder collaboration, skill-building, problem-solving, experimentation and crowdsourcing of collective knowledge. This model will also benefit from the emergence of tech communities, such as GovTech and CivicTech. This approach to government as a platform, more than any other, is influenced by questions and theories of democracy and requires not just public servant involvement, but also civil societal and partisan political pressure and momentum, to decide how government operates and define the nature of the relationship between citizen and state.

These models of government as a platform are not mutually exclusive; however, the most mature digital governments will link them together as a sequential, iterative approach in pursuit of conditions that enable agility, digital innovation and broader ambitions for open government.

Successful government cannot take place without the involvement of the population. However, while there are many opportunities for the democratic experience of government to reflect the cultures, and be reconfigured by the technologies of the digital age, such opportunities cannot be imposed by public servants but must, instead, emerge from a collective desire to renew democracy. Therefore, in order to facilitate any societal, democratically expressed rethinking about the relationship between citizen and state, governments must first create ecosystems to support service teams to meet the needs of citizens.

Building a “government as a platform” ecosystem

The shared platform model is not a new idea. The history of e-government is littered with shared services and technical interventions designed to offer common solutions to common problems, leading to assumptions that government as a platform is a new name for technology-driven interventions. However, under a mature digital government, the focus of government as a platform is not on individual solutions but rather on a holistic ecosystem that provides service teams with the resources to focus solely on the unique needs of their users.

“Government” is not a single entity but rather a collection of organisations and teams who work on designing, implementing and operating policies and the services they produce. These service teams with responsibility for meeting the needs of citizens may consist entirely of in-house capability, they may be outsourced, they may be a hybrid of the two or they may even be delivered by charities or private companies independently of any government contract. Nevertheless, it is their activity that forms theintermediary between government and users, and it is in support of their delivery that an ecosystem focused on common needs can abstract many of the issues which people would otherwise have to address.

Government as a platform is therefore not just a matter of deploying various technological platforms to enhance the user experience of a given service; it represents a more comprehensive approach to addressing challenges that might confront a service team who can then focus on the needs of users. Clear sources of data and transparency around access (see section 3), improved capability within teams and better access to suppliers – as well as guidance on how to deliver well and access technology and tools – will facilitate the delivery of public services more quickly and at consistent quality. These elements are essential to a joined up, effective experience of government for citizens when interacting with the state.

Table 4.1 identifies several important issues that could be addressed via government as a platform thinking. It shows that an ecosystem supporting service teams to meet needs (model 1) provides the foundations which can then facilitate the creation of a marketplace for public services (model 2) and a route to rethinking the relationship between citizen and state (model 3).

Table 4.1. Examples of elements in a government as a platform ecosystem

5 Open by default

A government is open by default when it makes government data and policy-making processes (including algorithms) available for the public to engage with, within the limits of existing legislation and in balance with the national and public interest.

Open by default in action

Drawing upon core digital government principles (OECD, 2014[7]), open by default stresses the proactive use of digital technologies and data by governments to enable more responsive, inclusive, accountable and agile public sector organisations.

Open by default helps governments act as platforms (see section 4), affecting the work practices and mechanics of public sector organisations and contributing to a radical change in organisational culture. A digital government is open by default when it shifts from top-down, centralised and closed decision-making processes – based on policy “black boxes” and driven by organisational efficiency – towards a more proactive approach (see section 7) centred around openness, collaboration, collective intelligence and innovation.

Open by default means communicating, informing, consulting and engaging with external and internal actors to co-create public value, crowdsource collective knowledge and build up public sector intelligence based on a design-led culture.In the initial stages of e-government, open by default drew upon existing policy frameworks for public sector transparency. Among others, it focused on leveraging digital technologies to enforce the right of citizens to request access to information on the activities of governments. The growth of the Internet saw government websites increasingly used to present public sector information (Power of Information Task Force, 2008[24]). The creation of e-government platforms enabled governments to develop and put in place online one-stop shops where citizens and businesses could obtain, and sometimes request, further information relevant for their needs and, eventually, perform operations and access government services

These efforts were accompanied by the digitisation of organisational processes within the public sector and the development of a paperless government. The aim was to tear down government secrecy and information asymmetry between the public sector and its constituents – although the process remained largely reactive at the public sector end.

More recently, since the early 2000s the explosion of social media has provided new digital platforms that governments can use to reduce the gap with their citizenry (Mickoleit, 2014[25]). However, governments often fail to acknowledge the value of digital platforms as instruments for multi-stakeholder engagement and collaboration, rather than simply as one-way tools to disseminate information.

The fourth industrial revolution has increasingly enabled and empowered citizens “to voice their opinions, co-ordinate their efforts and possibly circumvent government supervision” (Schwab, 2016[26]). Digital technologies are now present at the very core of citizens’ day-to-day lives, revolutionising the ways in which they interact and engage. Accordingly, government understanding of good practices in using digital technologies and data for public sector transparency – characterised by a reactive and passive approach– has shifted towards digital governments that are open by default, implying a more proactive use of digital technologies and data to communicate, inform, consult, engage and collaborate with citizens, partners and sectors both inside and outside government.

Open by default as a driver of inclusiveness

A digital government is open by default when it uses digital tools and data in a collaborative manner to proactively engage with stakeholders and place collective wisdom at the centre of a dynamic and interactive process of public sector intelligence creation. Once embedded in digital inclusion policies, openness by default makes decision making more user-driven (see section 6) and inclusive, and helps avoid new forms of digital exclusion. A digital government that is open by default can help make public policies and services more accessible to all by facilitating the engagement of those interested in joining-up government decisions, and bringing new perspectives to policy life and public service delivery cycles. It can help democratise decision making and allow a multitude of voices to be heard, making core government processes more inclusive, agile (e.g. ICT commissioning) and accountable (e.g. open contracting) (OECD, 2020[16]).

An open by default approach also affects the way in which public officials interact beyond their own sphere. While governments increasingly use digital platforms to communicate, inform, consult, engage and collaborate with a more digitally enabled society, the use of technology within the public sector has focused more on improving processes and less on building bridges between public officials to create champions for digital transformation. Such communities of practice and cross-government networks are now understood as vital to breaking down organisational siloes and delivering end-to-end solutions that respond to problems in a holistic manner (OECD, 2020[16]; OECD, forthcoming[15]).

Fostering a digital government that is open by default means nurturing a culture of learning from failures, as well as successful practices, regarding the use of digital technologies and data across the public sector. This approach helps make public sector organisations more digitally mature and prepared to manage potentially undesired results or expected challenges, as well as to scale up and replicate good practices as a means to accelerate positive change. This requires enabling government as a platform (see section 4) in terms of not only digital solutions but also human collaboration. Such scenarios may be obstructed by conservative and bureaucratic organisational cultures where fear of failure and compliance with the status quo dominate at the expense of agility, entrepreneurship and dissent. It is therefore essential to create safe spaces for the expression of concerns and ideas, where experimentation with new approaches to policy challenges are welcomed as a means to promote a digital government that is fundamentally open by default.

Openness by default includes enhanced and democratic access to key drivers of personal and collective growth and development. This is why digital government policies and strategies that encourage open by default approaches include provisions on open government data, API sources, open algorithms and open source. Priority is given to strategic actions that ensure digital technologies are at the centre of multi- stakeholder collaboration, so as to draw upon their scalability and potential multiplier effect. Examples include open datasets, open source solutions and multiple reuse cases, within legislative limits (e.g. privacy, data protection, confidentiality).

By opening up government data, governments are contributing a valuable strategic asset to foster public sector, business and civic innovation (Ubaldi, 2013[27]), and helping to build a data-driven public sector (see section 3). When reused, open government data become a valuable resource that can support governments in improving public service delivery, enhancing good governance, propelling the digital and data-driven economy, and empowering civil society to help keep governments accountable. In terms of the use and sharing of open source, during the initial stages governments can avoid vendor lock-in by promoting the adoption of open source software within the public sector. At more advanced stages, open source can increase the interoperability of services and data, promote digital innovation, help public contracting become fairer and more inclusive, and make market competition more balanced, thereby facilitating the emergence of new market players (OECD, 2018[28]).

Box 5.1. Open by default country practices

Urna de Cristal (Colombia)

The Crystal Urn (Urna de Cristal) is a Colombian government initiative that was launched in 2010 to promote electronic citizen participation and government transparency, and has since evolved into an open government portal. Since its inception, the initiative has consisted of a multichannel platform integrating traditional communication media (television and radio) with digital media (social networks, SMS and websites). These channels are made available to all national and territorial government entities to facilitate the creation of participative forums at all levels, with a view to improving relations between citizens and the state. Through the portal, Colombians can influence the decisions of leaders and become informed about government results, progress and initiatives. They can transmit their concerns and proposals directly to government institutions, and participate and interact with state management, services and public policies. This creates a binding relationship between citizens and the state.

GC Tools (Canada)

The GCTools Team within the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat created the GCCollab portal as a closed online collaborative platform, hosted by the Government of Canada, where Canadian public servants (federal, provincial, territorial and municipal), academics, students and other parties can communicate, exchange ideas, co-create content, collaborate and establish communities around specific topics of common interest. The GCTools Team has also created similar initiatives including GCconnex (a professional networking platform) and GCpedia (a wiki-based platform for knowledge sharing) that are available exclusively to federal public servants.

The development of these platforms followed an iterative and incremental approach, which has broadened the scope of collaborative options available to users and their degree of openness. GCPedia was developed first, followed by GCConnex and, most recently, GCCollab; however, while GCPedia enabled crowdsourcing for documents, the platform did not supply discussion forums. GCConnex expanded collaborative options with blogs, discussion forums, polling and more, but was only open to federal public servants. GCCollab builds on these two platforms, and allows also users from outside the federal public service to participate.

Developing a national open government data infrastructure (Mexico)

The development of the MX Open Data Infrastructure (Infraestructura de Datos Abiertos MX), or IDMX, consisted of an online, open survey designed to identify datasets that users believe have a significant impact on their daily lives. Participants contributed suggestions and voted for the datasets they wanted to see released as open data – an approach that made the exercise more open and inclusive in relation to its predecessor in 2015 (where a predefined list of datasets was made publicly available for voting). The IDMX contributes to the implementation of the open data policy in Mexico, which aims to balance data demand and provision as a mean to enable the creation of public value.

Open source policy (France)

The Policy of Contribution to Free State Software (Politique de contribution au logiciel libre de l’Etat) focuses on assisting public sector organisations to open up sources code and encouraging public servants to introduce changes (precisions or amendments) to existing contributions. The policy establishes rules and principles for opening up sources code, offers a set of best practices in terms of free software and defines a governance approach to better manage contributions.

- User-driven

A government becomes more user-driven by awarding a central role to people’ needs and convenience in the shaping of processes, services and policies; and by adopting inclusive mechanisms for this to happen.

The evolution of user-driven approaches

A user-driven approach describes government actions that allow citizens and businesses to indicate and communicate their own needs and, thereby, drive the design of government policies and public services. Such an approach accords with citizen and business expectations that public services should be designed according to their needs and be adaptable to different user profiles.

Digital technologies have changed the ways in which citizens interact with each other and their governments. User-driven approaches build on the value of digital technologies and data to spur broad public modernisation initiatives through the integration of technology into service design and delivery and the shaping of public policy outcomes. It paves the way for governments to achieve efficiency and productivity gains through new forms of partnerships with the private and third sectors, or to crowdsource ideas from within their administration and society at large (see section 4 and section 5).

Government notions of policy and service design and delivery have evolved in tandem with advances in digital technologies. Today, digital technologies allow governments to enter into two-way communication flows that permit citizens or businesses to customise and design services that meet their own needs. User research, user experience design and human-centred design all explore how to incorporate the user-driven approach into policy and service design and delivery (OECD, 2020[16]).

Governments have shifted from government-centred approaches (focused on increasing cost reduction, efficiency and productivity) to more user-centred ones (focused on interpreting user needs to improve administrative and personal services), before finally transitioning to user-driven approaches (focused on placing the needs of the users at the core of digital transformation processes in order to improve quality of outcomes and create increased public value). However, user-driven approaches do not negate earlier efforts; indeed, the process is iterative building on each stage to achieve greater collaboration.

The rationale for moving towards user-driven approaches

The term “user-driven”, while by no means ubiquitous, represents an evolution in the concepts user- centred or user-centric. The recent convergence of digital technologies and citizen engagement practices has driven an evolution in government engagement, involving citizens in the creation process in ways that extend beyond user-centric approaches. “User-centred” implies a user that is more passive and waiting to be engaged reactively, while user-driven describes a more active, embedded role. User driven approaches advocate for:

- government platforms and engagement mechanisms that invite two-way communication flows and collaboration between public servants and citizens and businesses (see section 4 and section 5)

- citizens and businesses being as open and active as possible in communicating with government (see section 5)

- government providing services that are simple, less bureaucratic and provide genuine public value (see section 7).

Key elements of user-driven approaches

Engagement by default

User needs should form the basis of the design and delivery of user-driven digital services. In order to obtain digitally transformed public services, citizens and businesses should be engaged and involved from the beginning, allowing service designers to reflect their views, needs and aspirations. The user should be present during the entire service lifecycle through service design, development, implementation, delivery, monitoring and re-design to enable co-creation between the user and government (see Figure 6.1).

Figure 6.1. An agile approach to government and public interactions during policy making, service delivery and ongoing operations

Learning

User research and service design are powerful tools to explore how to balance the needs of users with the reality of government’s need for greater efficiency. Privileging a user-driven approach can help:

increase awareness of public service design processes

encourage others to do the same – businesses, other governments and non-government agencies

– in order to spur collaboration

encourage feedback loops that allow for more user insights and lead to better design and service delivery.

Accessibility and inclusion

User-driven approaches can facilitate understanding of the reality of user needs, their motivations and their expectations. If user research is conducted properly and adequately, users will feel empowered to participate, and will have access to appropriate channels to communicate with the government when, and if, accessibility and inclusiveness fall short. As governments increase accessibility of services, by being user-driven, they inherently become more inclusive.

Talent and leadership

User-driven approaches will require cultural change and adequate capabilities in the public sector (OECD, forthcoming[15]). Public servants will need to understand how to conduct and use user research. Leadership is essential to encourage this process and fully exploit its potential. Training approaches will need to be

developed to help public servants understand how user research enriches their work, and to ensure that service teams are equipped with the necessary skills. Leadership will also need to authorise, incentivise and nurture a different mindset. Working in the open, collaboratively and with greater transparency, is crucial to ensuring that two-way communication channels operate effectively.

Politically, governments will need to accept a shift in the balance of power. Citizens involved in user-driven approaches will have more power to effect change and, as a result, will feel closer to governments through their involvement and integration into policy-making processes and the service design and delivery cycle. This involvement will require additional time, and governments will need to demonstrate that user input has been heard, acted upon and reviewed.

Service design and delivery

One of the most important policy outputs that will benefit from user-driven approaches is service delivery.

Siloed government service delivery approaches, with multiple and sectoral public sector websites and fragmented service delivery, reflect internal institutional structures. They are incompatible with providing simpler and more convenient services. Users increasingly expect services that are seamless, integrated and accessible via multiple channels as well as customisable. The delivery model for government services should allow the user to easily identify the services they need through the channel they find most convenient.

Through intelligent reuse of data and information previously generated and/or provided by citizens, governments can shift from reactive service delivery approaches to proactive practices (see section 7). In reactive environments, the citizen is responsible for initiating the service demand, identifying themselves and providing the required information. In proactive environments, the public sector knows its citizens, understands their socio-economic condition and current needs, provides them the space to voice and signal their requests and preferences, and is able to deliver a service before a request is made.

This trend in the governance of digital service delivery stems from a clearly identified need – making services simpler, more accessible and responsive to needs, all of which are possible with a government that is digital by design.

More and more countries are developing government Digital Service Standards to improve the quality of service delivery. The one common element in each case is that user needs are articulated as the point of departure. Such is the case in the digital services playbooks of Australia, Germany, the United Kingdom and the United States.

Linkages with the other dimensions

Establishing this culture and set of expectations at the strategic level, among those governing and directing digital government efforts, will help to propel user-driven approaches and embed user needs throughout policy processes. However, it is important to ensure that digital transformation do not contribute to digital divides. Policy levers can be designed specifically to avoid this scenario and to preserve access to services for users according to their needs in place of blanket implementation of digital as default (see section 2).

With the expansion of Internet usage, businesses and governments increasingly shifted away from analogue paper procedures to online processes, exploiting its potential to send information quickly to citizens. Over time, this unidirectional approach has been supplemented and even replaced by direct, two- way communication. Online communities where customers can share ideas and provide feedback have become the norm in the private sector and are increasingly recognised as a means for government to encourage inclusive collaboration with the public (see section 5).

Governments can play an enabling role in encouraging citizens to work with policy makers by developing resources and tools to scale such efforts. The availability of a digital government ecosystem that reflects

an understanding of the needs of citizens and businesses in a scalable, coherent and effective fashion, supports the development of user-driven services (see section 4). Subject to the emergence of societal and democratically expressed efforts to rethink the relationship between citizen and state, the government as a platform approach can be developed further to herald an ever more co-operative, collaborative and user-driven approach to services and policies.

Beyond the direct involvement of users, citizen-driven approaches will enable governments to use the data of citizens and businesses to better deliver public services. The exchange of data across sectors and levels of government (see section 4) enables public service providers to maintain an up-to-date overview of the life situations and related needs of its citizens, allowing for more tailored digital service provision. The proper combination and use of data forms the basis of the shift from reactive to proactive service delivery

(see section 7).

Box 6.1. User-driven country practices

Youth Action (Canada)

On 13 February 2020, the Prime Minister of Canada announced the launch of cross-Canada consultations on a first-ever Youth Policy for Canada. The website details a number of ways in which young people can share their views, including by answering questions on matters of interest, participating in online discussions and posting video comments.

https://youthaction.ca

Participa (Mexico)

The government website gob.mx/participa makes available digital tools that encourage citizen participation throughout the public policy cycle of the federal government.

Carpeta Ciudadana (Spain)

In Spain, carpeta ciudadana (Citizen folder) facilitates greater connection between citizens and the public sector. It provides citizens with a simple, single point of access for the Spanish public administration in order to gain information on current operations and procedures. Citizens can also directly contact the responsible public institutions to obtain updates.

https://sede.administracion.gob.es/carpeta/clave.htm

7Proactiveness

Proactiveness represents the ability of governments and civil servants to anticipate people’s needs and respond to them rapidly, so that users do not have to engage with the cumbersome process of data and service delivery.

What does proactive government look like?

The digital age has led users to expect service in convenient, timely and expedient ways. This is particularly true for our experiences with the giants of the Web – Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon – which dominate the digital market and have familiarised the world with easily accessible services. Such convenience is a product of the data generated by users of those services, which is then analysed to better understand preferences and habits with the aim of better responding to demands based on profiling and anticipation.

A proactive government pre-empts requests from citizens, instead providing answers or solutions to their needs through the adoption of push vs pull delivery models (Linders, Liao and Wang, 2018[29]) that limit to the minimum the burdens and frictions of interacting with public sector organisations.6 Proactiveness builds upon the five previous dimensions and aims to offer a seamless and convenient service delivery experience to citizens, shaped around their needs, preferences, circumstances and location, on the basis that governments are equipped to anticipate and address problems end-to-end rather than through a fractured and reactive approach.

This dimension encompasses, among others, the capacity of governments to gather real-time insights into users’ needs and preferences, to proactively request feedback from users and incorporate them into “feedback loop” mechanisms, and to ease citizens’ access to real-time information on service delivery (e.g. through smartphones apps and dashboards) in order to engage with them.

Successful proactiveness in service delivery relies heavily on organisational capacity to engage with data. This is why establishing the conditions for a data-driven public sector is an essential enabler for a proactive government to flourish (see section 3). Data on insights need to be easy for government to consume as a starting point for new actions or important activities. Public sectors organisations need to make sure that insights gathered from users (either through the provision of explicit feedback or generated through service use) are communicated across the administration so that public sector actors can use them to interact, share, learn, and be kept up to date in an easy and timely fashion. For this to happen, the necessary safeguards around data ethics, protection and consent must be understood and in place (see section 3). Furthermore, all decision makers, not just data analysts, must be able to access these insights in ways they can comprehend. Leaders need to be able to share and discuss those insights and act on what they have learned.

The rise of automation has enabled data consumption to become a reality. Additionally, the growth of mobile government and the increased use of mobile devices and apps is a perfect way to feed automated AI-driven alerts to civil servants in the event of changes in user data relating to services for which they are responsible – and allowing them to make adjustments in a timely manner (OECD/ITU, 2011[30]). Such access to insights is immediate, unmediated and timely, eliminating the need to search reports and dashboards for information.

Proactiveness as a vehicle for enhancing public trust

Even though governments do not need to attract and retain customers, as is the case with businesses, the level of citizens’ satisfaction with public services matters as a means to reinforce trust in governments and the capacity of public authorities to respond to their needs. Public services constitute the most direct and immediate contact that citizens have with their government. Providing users with a seamless and satisfactory experience when using services, and ensuring that their needs have been anticipated and appropriately addressed, is the best way to grow users’ confidence in the agility and responsiveness of public authorities, and to reinforce the legitimacy of government actions. This issue will become particularly challenging as people move across borders and have the chance to select where they want to access a specific service, and as the level of segmentation and sophistication of the community of users becomes increasingly diversified. Reaching users and convincing them to use a new digital channel is not enough and should not be the primary focus. Instead, getting people to engage and connect with a service, obtaining insights into their preferences, and anticipating and addressing their needs is crucial to building a strategic approach to service delivery and leveraging the digital transformation to improve the functioning of the state and its relationship with the citizens.

A new paradigm for the next generation of public services

The rise of artificial intelligence and machine learning are just some of the paths available to governments to enhance proactive and anticipatory governance as a way to enable the next generation of public services (Ubaldi et al., 2019[13])). Fostering a new model of proactive government demands a strategic approach that will move the public sector towards models that are more data-driven, digital by design and function based on a government as a platform paradigm (see section 4).